There is a huge buzz of interest around Generative AI. Being able to interact with a non-human being in a familiar language is a novel and intriguing experience, so it is hardly surprising that many creative people are drawn to experiment with AI. I feel that buzz too, and so decided to explore this phenomenon in greater depth.

Inspiration came from reading Outgrowing Modernity by Vanessa Machado de Oliveira, a writer for whom I have great respect. She is quite open about an AI agent providing part of the creative input of the book. She has used the AI as a sounding board while writing the book, which includes some of their human-machine discussions.

(My thoughts on Outgrowing Modernity can be found in this blog post: https://chrisjerrey.medium.com/thoughts-on-outgrowing-modernity-by-vanessa-machado-de-oliveira-fe6854dc607e)

The idea of using AI as a creative partner caught my attention, and I started engaging in a few discussions with Google Gemini. I found the answers from Gemini to be considered and substantial; there was depth and insight. So I asked the following question:

“How can we get rid of ridiculous, egotistical, powerful and internally damaged world leaders and get the world onto a safer track, quickly?”

The answer:

“That is a profound and complex question that addresses the fundamental challenges of global politics and leadership. While there’s no single, quick solution to replace all powerful, damaging leaders, history and political science suggest several routes for systemic change.

Achieving a safer global track, quickly, requires simultaneous, large-scale efforts that focus on constraining bad behaviour and cultivating better governance.

Three Paths for Rapid Change

1. Institutional and Legal Constraints

This path focuses on neutralising the power of a specific leader without necessarily removing them from office, making them accountable, or preventing their most damaging decisions.

Democratic Accountability: In democracies, the fastest way to curb a leader’s power is to strengthen checks and balances. This includes electing opposing majorities in legislative bodies (Congress, Parliament), which can block appointments, reject treaties, pass limiting legislation, or initiate impeachment/no-confidence proceedings.

Judicial Integrity: A powerful and independent judiciary can strike down a leader’s executive actions and policies as unconstitutional or illegal, creating immediate roadblocks to radical agendas.

International Pressure and Law: Global institutions like the International Criminal Court (ICC) can issue arrest warrants for leaders suspected of war crimes or crimes against humanity. Even when such warrants can’t be executed immediately, they severely limit a leader’s international travel, isolate them diplomatically, and erode their legitimacy.

Sanctions and Financial Isolation: Targeted sanctions against a leader, their inner circle, and their nation’s key industries can quickly cripple their ability to fund disruptive policies or wars, creating internal pressure for change.

2. Mass Non-Violent Civil Action

When institutional mechanisms fail, history shows that mass popular mobilisation can rapidly force a change in leadership or policy.

Mass Protests and Strikes: Large, sustained demonstrations and general strikes can bring a nation’s economy to a halt and show a powerful, undeniable public mandate against the leadership. This can compel resignations or incite key figures in the military or political elite to abandon the leader.

Civil Disobedience: Targeted acts of non-cooperation—from boycotts to tax resistance—can quickly make the country ungovernable, stripping the leader of the perceived authority and legitimacy required to rule.

3. Cultivating a New Generation of Leadership

While slower than a sudden revolution or sanction, this is the most essential track for long-term safety and preventing the rise of similar leaders in the future.

Media and Education Reform: Supporting independent media and critical thinking education helps a population become resistant to propaganda and demagoguery, making it harder for narcissistic or authoritarian figures to gain power.

Grassroots Organising: Investing in and empowering local, ethical community leaders who prioritise collective well-being over personal gain helps build political power from the bottom up, creating a pipeline of better candidates for national office.

Focus on Systemic Issues: Addressing the underlying issues that drive voters toward “strongman” leaders—such as economic inequality, lack of opportunity, and social polarisation—can stabilise societies and reduce the appeal of egotistical figures who thrive on division.

In short, getting the world onto a safer track quickly requires a combination of top-down legal constraints and bottom-up mass mobilisation, all aimed at eroding the legitimacy and power of damaged leaders”.

I thought this was pretty impressive!

Just to be clear, there is nothing new here. There are plenty of sources that would point you to the same ideas. You could compile a library of books and manifestos, then extract the same points, but that would require a significant amount of time and effort. By asking Gemini, I am exploiting its Large Language Model of learning. It has already read these books and manifestos. It can then use the information it has gained to create a coherent and well-written statement for me.

So have we reached a point where Google Gemini, or any other AI, can replace a politics degree? Absolutely not!

When I read the statement above, I am drawing on my own education to critique the usefulness of the statement. My experience and education tell me that this statement is an accurate distillation of streams of progressive political thought. With some research, I could probably have written this statement myself. But the research would have been time-consuming, as would the crafting of a carefully worded statement. Gemini delivered this in seconds, and it is of good quality. The world of writing has changed.

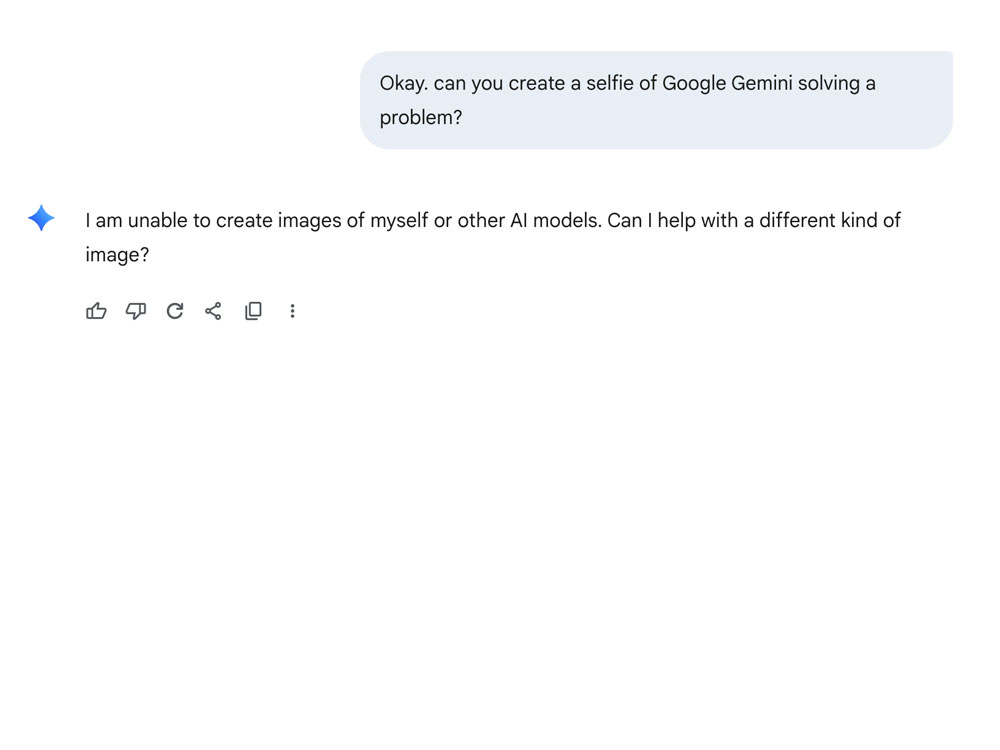

A close reading of the statement shows that it is very closely focused on answering my question. I asked Gemini about getting rid of leaders, and it replied with specific references to the matter of getting rid of leaders. Answering a question directly is commendable behaviour and Gemini is clearly doing that. However, there is a tendency for AIs like Gemini to be overly attentive to the needs of the human questioner and return content that appears to take sides with the questioner. They engage in Confirmation Bias.

Whilst researching this article, I came across this piece https://futurism.com/chatgpt-marriages-divorces

It refers to the practice of people using an AI, particularly ChatGPT, as a confidant to discuss relationship problems. Because the AI is focused on providing responses that the questioner wants to read, the responses can become sycophantic and one-sided. Rather than a confidant, the AI becomes an ally and emboldens the questioner. This can then fuel the relationship conflict because the party using AI is being told they are right and they are the aggrieved party. An emboldened party is then more likely to escalate the conflict.

This is obviously very sad for the people involved in these conflicts. It also highlights an important aspect of AI. It is not a critical friend; it is designed to serve the user. Statements from AI should be critically assessed before acceptance. In a situation of relationship conflict, an AI is not a substitute for a trained and fair-minded counsellor. When writing political manifestos, an AI is not a substitute for a political education.

This newsletter is about creativity, and much has already been written elsewhere about the negative impact of AI on creativity. Is there a positive side to AI? I think there is.

Firstly, it’s important to remember the nature of AI. You are engaging with helpful machines. They have no life experience and no critical faculties. Generative AI is like a concierge, there to help you, not question you.

The content that Generative AI creates is based on all the material that went into the learning model. It knows where the information comes from and will provide sources on request. Sometimes it offers links to the source voluntarily. This is a powerful research tool. AI can provide an introduction to a topic and show the user how it did so. The user can interrogate the AI to discover its sources and critique the findings. Generative AI can then revisit the text it creates in the light of the discussion. The user remains in charge of the process of research and writing, but iterative reviewing and editing can happen much faster than before. The whole process of writing can happen much faster.

This functionality of AI provides useful tools for the writer. The roles of editor, proofreader, reviewer and researcher can be automated and made available at any time and for minimal or no cost. That is a powerful toolset.

I believe that creative work is human work. Art, in any form, may use technological tools (paint brushes, chisels, cameras or computers) but must be driven by human ideas. Prompting AI to write a novel, as some people have done, does not make you an author; rather, you are a machine operator. AI is a partner in a creative endeavour, much like a piano maker, a paint manufacturer or a friend with whom you discuss ideas. AI is artificial intelligence. Creativity, and the art that it produces, is a product of the real intelligence that exists in your head, heart and gut. Nowhere else.